Page of Dossier for War Office

In September 1944 the Hofoku Maru (http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?59634), one of infamous Japanese transport ships (hellships), suffered aerial bombardment from the Allies. Among some 150 prisoners rescued, about 60 were British POWs from Thailand, including men from the Royal Corps of Signals. Interest in their accounts was intense. The War Office planned to debrief each survivor to try to ascertain the fates of the 40,000 British troops missing in the Far East.

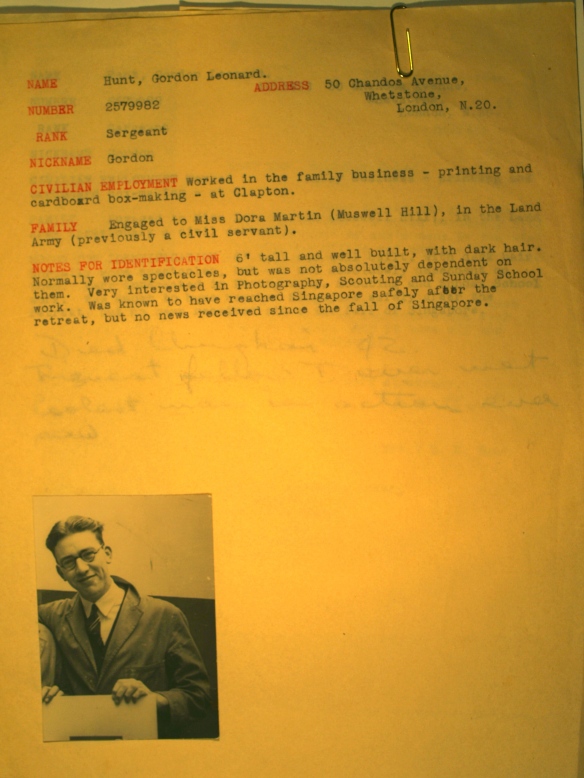

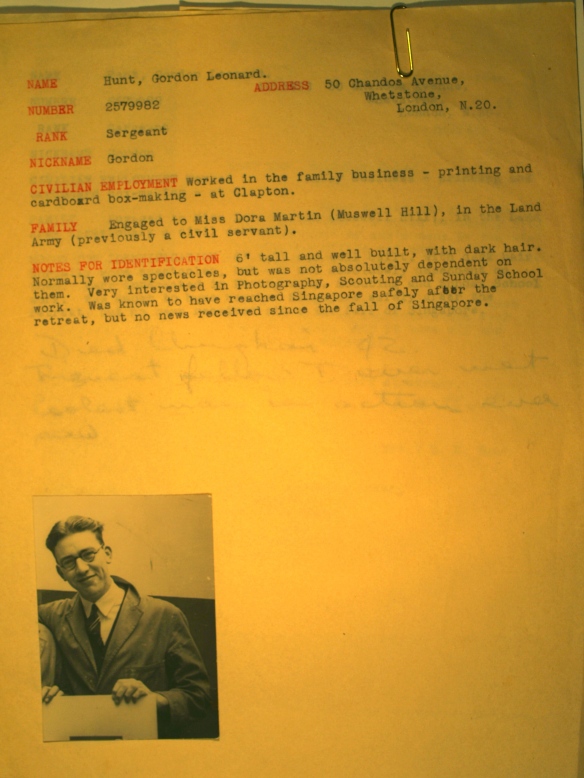

Phyllis, thinking about Barry’s men, contacted the War Office. She realised the immensity of their task in finding out about the thousands of missing men from the few rescued individuals. With the help of Queenie, the wife of Lieutenant Robert Garrod, she decided to compile a dossier with personal details and if possible photographs of the men in 27 Line Section for use in the debriefing sessions. She wrote to relatives the replies flooded in.

Dear Mrs Baker,… it does certainly help to know that someone is personally doing their best for us. … Your heart must ache many a time like mine and we can only pray for strength to bear it. I am enclosing a snap of my husband [George] taken in Malaya soon after they arrived there, I have marked my man with a cross. He is of average height about 5’5” and of a slim build. His hair is medium brown and blue eyes. The only prominent feature is his nose, which is rather big.

In civilian life my husband was employed at John Walton’s Bleach-works, a firm which belongs to Tootal, Broadhurst, Lee, Co. Ltd., but which always goes under that name. His dept at that time was Anti-Crease, you will remember Tootals Products are famed for their crease resisting properties, that was a part of his job, treating the material to be crease resisting.

(George had already died on the Railway, probably of dysentery, on 8 August 1943)

Dear Madam I am writing on behalf of my sister Mrs Bamford as her and her husband is no scolar and I have to do all the writing for them, now in regards to her son William Bamford which is a prisoner his Mother had a card from him last July 1944 to say he was alright working with pay … as far as we know he had no nick name just Willie he did not speak very clear the last time we seen him but he had false teeth before he went oversea but we did not have the pleasure of seeing him with them in before he went away, … now I do hope and trust you may be able to send his mother some good news concerning her son as he is their only child and they are just living for their boy.

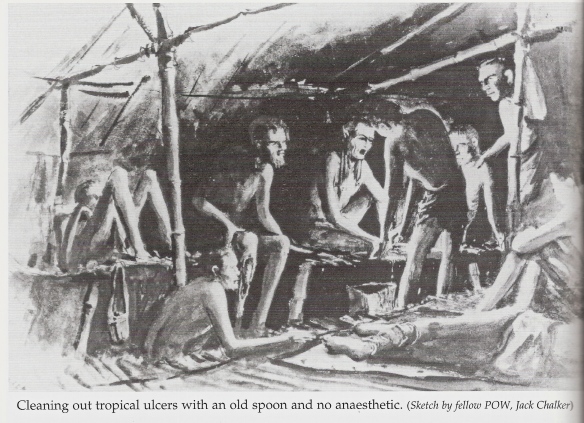

(Willie had already died of septicaemia from a tropical ulcer in Tha Khanun on 30 September 1943. Willie was, according to another POW, a: ‘Good kid, 100% well liked by everybody. Died quickly’.)

Sometimes the information was lost in an outpouring from desperate relatives.

Dear Madam, In the first place I am not very good at letter writing, so I must ask you to excuse me if this is badly written…

He is my Grandson and I brought him up from a Baby having lost his mother and father. and unfortunately I lost my Husband so I was forced to put him and his brother into the National Childrens Home and he had just finished serving his time at the printing Trade, when he was called up. so I don’t think I have seen him for about 3 1/2 years. in the first place he was sent to Malaya, and no doubt you know what happened their, when the Japanese got their. So having received that card at Exmas it is a little bit assuring don’t you think so, although they are such a long time before they reach you, one never knows as they are not dated, as their is a person who lives close by me, and I believe her Husband is in Siam well he wrote her a card in May and she has only just received it. But I must tell you that I send him a Japanese P.C. one a fortnight and I address it as this. A.H. Newton 2361041. Signalman, British. P.OW. Sandaka. Borneo, and I also have to put my address, but of course whether he receives them or not that is another matter, but it is not for want of trying for I do my best. and occasionally I write to the Red Cross in fact I sent to them at Christmas asking them to put a message of 10 words through for me so you see I am not backward in doing all I possibly can to try and let him hear from me.

I am every so sorry for the Relatives and friends of all those poor fellows that were on that Ship In fact for all those who are going through such a terrible time in this bitter cold weather, it is Heartacheing when you think of it all. not only our poor fellows but all of them, that has been done to Death, I sometimes wonder why God lets such things happen, although we have been bombed out of our home, that is nothing compared to what they are going through. I am sorry to say that I only have one Photo of my Grandson and that I cannot spare, but I have one that was taken at the Home if you would care to see that. Well I think I have told you all I know, and I wish I knew more, but I do hope what I have said is correct so I will just go on living in hopes and trust in God and pray that we may come together in not so long a time so wishing you all success in your most trying work…

Phyllis extracted all the information from the letters and made a page for each man (including many not on 27 Line Section). Finally, on 12 January 1945, Phyllis went to the War Office and handed in her dossier to a Mr Rogers. He did not know this at the time, but he was going to hear a lot more of Phyllis between now and late 1945.

More pages from the dossier.